The price of chicken is set to skyrocket. This information is not new (see here at The Straits Times and The Newpaper among others) but surely, there is more to it than affordability? Could this unprecedented surge in prices be indicative of bigger gaps in our food system, and could it lead to other bigger, more concerning problems?

With a per capita consumption of 36kg of poultry (as of 2020 – that means on average, every person in Singapore individually consumes that much chicken in a year), chicken is the most widely consumed meat here in Singapore. Yet most of us, especially the younger generation, know little about it, having grown up in a “post-kampong era”.

The price surge in poultry has been attributed to rising chicken feed costs, but what exactly do chickens eat?

Soy and corn: the driving force behind the price hike

Poultry feed is made primarily of soybeans and corn, both of which are infamous for causing deforestation. There is no shortage of literature detailing the vast adverse impacts of animal agriculture on the environment so this article will not be delving into it. The rearing of livestock requires large amounts of feed, which forests, grasslands, and savannahs are cleared to plant. In fact, most of the grain we plant is fed to animals, not humans, as unpacked over at One Green Planet.

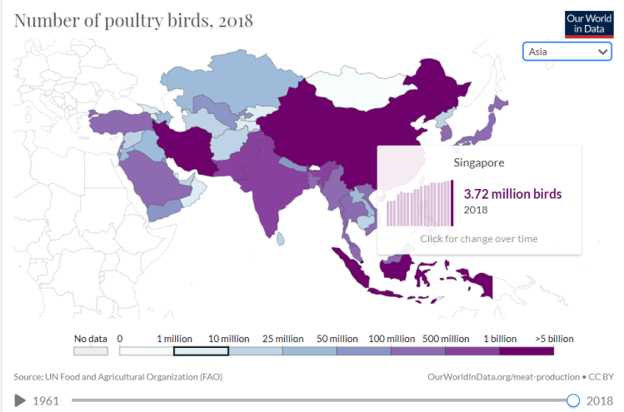

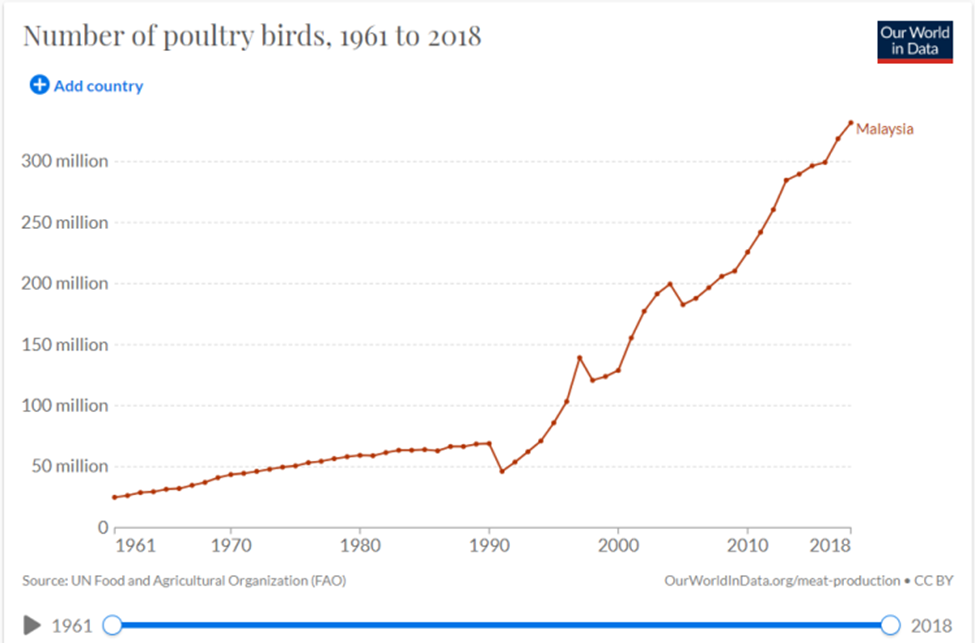

As demand for soy and corn rises to unsustainable levels, their prices begin to climb. Despite the prevalence of poultry here in Southeast Asia, the majority of soy and corn is imported, since the 2 crops require cooler, temperate climates to grow. Singapore’s main supplier for chicken, Malaysia, does not produce soybeans at all, importing soy meal to feed all of the 331.79 million chickens (as of 2018) reared.

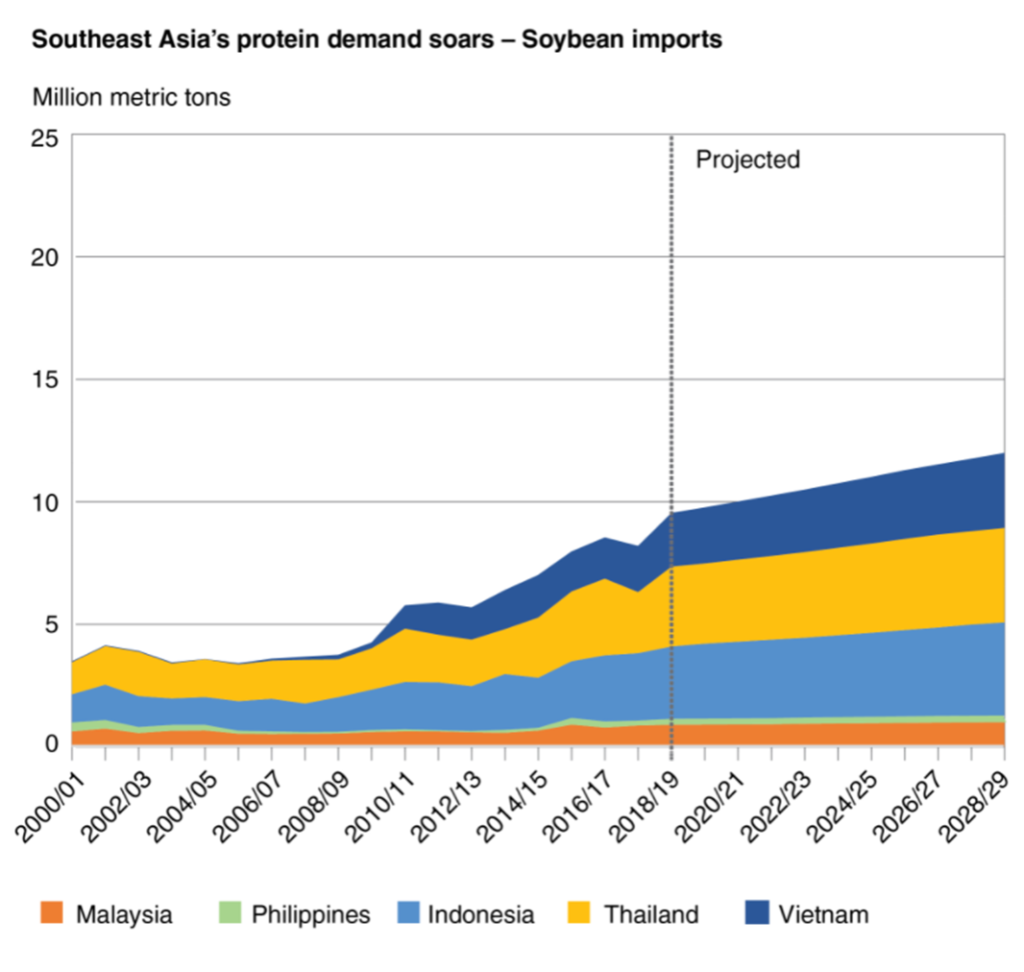

Similarly, corn meal relies heavily on foreign supply as well. With Malaysia and Vietnam predominantly driving the growth in corn imports, Singapore’s demand for Malaysian poultry directly contributes to the adverse environmental effects caused by corn production. By 2028, the 11 Southeast Asian countries alone are projected to account for a third of the global soy meal import share, with imports for soy feed tripling from 2000 to 2018.

Source USDA, Office of the Chief Economist, USDA Agricultural Projections to 2028

Current global demand for soy and corn is so high that Brazil, the world’s number one soybean exporter, had to instead import soybeans after selling too much. There is simply not enough land and resources to farm enough of these crops to fuel the exorbitant number of chickens consumed and/or wasted, leading to a shortage in supply that drives costs up.

Supply chains are also further stretched by increasingly erratic weather conditions brought about by climate change. With La Niña weather patterns developing, crops are greatly affected, lowering the yield of soy and corn.

Indicative of bigger problems?

Crashing food supplies

The increase in chicken costs have in part highlighted our rapidly growing demand for it, which, ultimately, is unsustainable. Livestock rearing on this scale simply puts too much pressure on our food systems. Should we continue eating the way we do, projections show that overall food supply (consisting mostly of crops that are fed to livestock) will have to grow by 70% from 2005 to 2050.

With forests twice the size of the UK having already been destroyed for soy and palm oil production to provide for present-day demand. If demand were to continue to increase, there would soon be no more forests and land left for us to exploit for food production. Meeting higher food demand in the future will literally become impossible, pushing many more into hunger.

It is likely that Southeast Asia’s chicken supplies will be one of the first to be affected by these effects. Our heavy reliance on foreign supplies of chicken feed to sustain chicken populations means that when shortages become more severe, our access to feed will be at risk. Our long food supply chain leaves us vulnerable to disruptions at multiple junctures, ultimately making our food system less resilient.

With more stakeholders involved in the food production, our ability to regulate our food is also compromised. For example, while sources and safety of the chicken itself can be monitored, it is difficult to trace the kinds of chemical pesticides that may have been used in the growing of feed in one or more different countries. Livable wages and working conditions of the workers upstream countries become more difficult to ensure as well. This creates a situation whereby we, as consumers, have less knowledge and say over our food systems, and thus no way to change it. We merely see the end product – chicken on our plates.

However, as we have discussed, the story of our chicken supply is much more complicated than what we think, with many more considerable factors that come into play. Is there a way for us to fix this?

Greater implications beyond price?

The increment in price is perhaps something the more privileged can afford, but what about the others? And what other significant problems arise out of this as well?

- Contributing to the death of the hawker trade

Operating on profit margins as low as 20 to 30 cents, many hawkers may not be able to afford to absorb climbing costs. Yet, passing it to consumers causes a loss in business, with hawker Douglas Ng’s fishball noodle stall experiencing a 40-50% fall in sales since increasing prices by 50 cents. This does not bode well for chicken rice stall owners who expressed the need to up prices should the current trend continue. Ultimately, the agricultural web affects not only the food we eat, but has bearing even on areas like cultural preservation. With rising costs eating up hawkers’ profits, it is difficult to imagine that more youth will be willing to join the trade and keep our hawker heritage alive.

On more tangible fronts, hawker food is one of the most affordable and accessible options available for us Singaporeans. With some stalls still offering a plate for as low as $2, chicken rice, in particular, is a staple meal for many low-income families. Rising prices of cheap hawker food will inevitably have a big impact on food security for many.

- Opening the floodgates to lowered safety standards

Getting desperate, some countries are turning to previously banned sources of crops to feed the growing poultry industry. For example, in India, in order to help bridge the need for feed, the ban on genetically modified (GM) soybean meal meal imports had been lifted for the first time. The growing popularity and widespread use of pesticide in agricultural farming was, to some extent, driven by a similar reason: an inability to meet food demand.

As said by Dan Barber, “You are what you eat eats” (too). These hint at a disturbing, yet very plausible future (and even at present), where such health/environmental compromises become necessary and rampant. These practices of using chemical fertilizers and pesticides become normalized with time, permanently altering the state of our agricultural web. And because of how disconnected we are from our food, we may not be aware of these changes in our food supply chain. Ultimately, pressures in certain agricultural sectors – in this case, soybean and corn production – affect every part of the agricultural web, having unseen effects on the quality of food that reaches our plates.

The pressure of unmeetable demand permanently altering food as we know it can also be seen in chicken demand’s influence on pork. Pork loins, as we know it, are closer to white than red meat, though heritage (“natural”) breeds (as pictured above) are “redder” and less lean. This change was a man-made one – soaring chicken consumption rates in the 1980s prompted corporates to breed and market pork as “The Other White Meat“, a substitute for chicken and turkey. As pig farming continues to pursue leanness and efficiency, flavor is slowly being bred away. This proves that pressures in one food source can drastically, and permanently, alter others.

Food insecurity

Foodbank Singapore defines food insecurity as the state of being unable to afford sufficient quantities of affordable or nutritious food. Indeed, the hike in the cost of chicken further contributes to this problem, potentially making this cheaper meat choice inaccessible to a greater number of households. Being food secure also entails the power of choice in the food one chooses to eat, and increasing food cost hinders our efforts as a nation towards that. Affordable, nutritious food should be a basic human right and provided to all regardless of race, language or religion. Apart from more tangible elements of choice, food insecurity is also the anxiety of not knowing when your next meal will be. With unstable food supply chains and increasingly volatile crop growing conditions, the prospect of more of us experiencing this form of food-insecurity-anxiety is becoming very plausible. Ultimately, food is an intersectional subject, and what we eat has effects not only on our environment, but on our community as well. Read on in part 2.

Cover photo by Thomas Iversen.